- Apr 30, 2021

- 9 min read

Updated: Jun 8, 2021

PHOTOGRAPHY AND BOTANY

the representations of

naturalism and humanism

TOYA LEGIDO

Universidad Complutense de Madrid

Since ancient times, humans have used plants for curative purposes, but with the emergence of scientific expeditions, they have also been reproduced and collected to be marketed. With travels to other continents, nature goes from being lived to being conquered.

The idea of the environment as an available resource for human use grew in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries under the Enlightenment project. Western man, with the mission of civilizing and bringing progress to all places on earth, started to domesticate, order and archive nature. Such inventory was carried out through the collection of herbaria and the creation of botanical illustrations. Through them, science established a biased view of what nature was, turning plants and animals into an object of study on which to intervene. Furthermore, it should not be forgotten that the western gaze and the scientific mediation on the habitat of “the others”, opened the way for its possible exploitation, by naming it, studying it and classifying it.

The idea of the herbarium, as a catalogue of specimens, can be found long before illustration; it appears in some of the first books that gather botanical representations in the 16th century, such as the “Treatise of the drugs and medicines of the East Indies” (1578), by Cristóbal Acosta. In these specimens the plants were described in a summarized way and were accompanied by a simple illustration made by means of a wood engraving. These compendiums were made with a descriptive and synthetic iconography so that traders could quickly identify the species. In addition, they were small-sized so that they could always be carried with them. We could say that it is the beginning of what today is understood as pocket manuals or dictionaries.

According to Daniela Bleichmar, “the Spanish natural history expeditions of the 18th century acted as projects of visualisation, making nature mobile, knowable and governable… In the Hispanic world, the enlightenment renovation was considered as a way to reinstate a more prosperous imperial situation, through a connection with the successes of the past, as a botanical reconquest.[1]

Thus, not only Spaniards but also all Europeans began to develop a large inventory of species from other continents, which could be rapidly transformed into exchange value. This was the reason why the great scientific expeditions from the 17th to the 19th century were subsidized, and also the reason why Botanical Gardens, Natural History Cabinets and many of the World Exhibitions were created.

Due to its scientific purpose, the documentary intention will determine, both aesthetically and conceptually, the character of the herbaria from its origin. The representation of plants, conditioned by the need to make irrefutable content visible, has always shown the morphology of type specimens in a summarised way, regardless of whether they were illustrations, engravings, frames, photographs or scans. However, the creation of this type of images has often been done through drawing, even after the discovery of photography. This may be because historically, the times spent creating illustrations were longer than those spent taking photographs. In the process of drawing, the long spaces in which the image is constructed serves to analyse and synthesise the taxonomy of plants, at the same time that they prioritise the representation with its essential parts. Perhaps, for this reason, botanists continue to use illustration as a didactic resource when describing specimens, although they are accompanied by photographic images to document them.

Reviewing photography history, we can see that the representation of plants was mostly influenced by scientific illustrations, rather than pictorial still lives. Examples of this are shown by classic authors, such as Anna Atkins or Karl Blossfeldt. Contemporary photographers also work on this simplified and minimalist line that enables a better understanding of flora morphology through a stylistic cleanliness. For example, artist Jimmy Fike, in his series “Fields of visions” (2020), presents a herbarium of edible wild plants found in his environment. Through a long selection process and through the help of digital software, he created a 'type' version of each species, in which he solely kept colour information in some of its parts. The author thus places the focus on what should be named. This idea of selective colouring is already found in many of the ancient botanical plates, in which its creators, to maximise production on expeditions, only coloured the essential in situ.

(left) Water Lily, 24" x 20", Archival Pigment Print, 2020. | (right) Canadian Violet. 11" x 14", Archival Pigment Print, 2017 |

© Jimmy Fike, J.W. Fike´s Photographic Survey of the Wild Edible Botanicals of the North American Continent.

Courtesy of the artist.

In a certain ironic way, in the series “Disassembly” (2012-14), artist Bownik reminds us of the torture that plants are subjected to, for the sake of science, showing us a herbarium that evokes taxonomic drawings and in which human interventions are exposed. Through the separation of the parts and its reconstruction through all kinds of artificial materials, such as pins, rubber bands or ropes, he demonstrates that in order to achieve the perfection of beauty, plants also have to undergo a plastic surgery full of artifice.

His images share the simple aesthetics that characterize the history of botanical representation, where clean and neutral backgrounds are used to isolate the specimens from their natural environment.

Placed in such an aseptic artificial environment, plants have been studied for centuries, away from the entire ecosystem that makes their survival possible. Thus, the representations of life and nature gradually became representations of death and artifice. For this historical reason, some contemporary authors return to the idea of contextualising botanical representation in their original environments, proposing an alternative to scientific studies that present flora as an isolated catalogue of specimens. For example, artist Javier Valhonrat, inspired by the tours through the Majorcan mountains that Archduke Luis Salvador made in the nineteenth century, develops the project “La senda y la trama” (2014) [The path and the web] and presents panoramic views that include, in camouflage, the scientific names of the different entomological and botanical species that inhabit them. In this case, and unlike classical herbaria, the specimens are not uprooted and isolated from their natural environment, but are simply named within it.

It is true that attributing plant species with commercial value has produced great environmental impacts, even leading to the extinction of many varieties. But it should also be noted that, precisely because of the enormous environmental impact of the Anthropocene, many species would have completely disappeared had they not been classified.

As Robert Watson explains, never before has the biosphere been under such intense and urgent threat. Deforestation rates have skyrocketed as we exploit the land in order to feed more people; global emissions are altering the climate system; illegal trade has eradicated entire plant populations, and non-native species are outnumbering local floras. Ultimately, biodiversity is being lost locally, regionally and globally.

Faced with this catastrophe, the cataloguing of vegetables seems essential for their preservation. Two hundred scientists from 42 countries have written a report on the state of plants, calculating that 4 out of 10 plants that exist in the world are in danger of extinction. Currently, it is estimated that only 1 in 10 plant species of the 250,000 described in the world is in danger of extinction. This means that the cataloguing and representation of plants has helped to keep some of them alive. Therefore, in this situation of extreme environmental disaster in which we are immersed, it is essential to promote all kinds of studies on the plant as a method to safeguard them.

Every year, as some varieties go extinct, others are named and described as new. Valuing the need to conserve the planet's biodiversity is an urgent matter in which some artists are also engaging. Many contemporary photographers, who work with herbaria, collect the technical language and strategies developed by science to represent different varieties; but the difference between scientific representations and those made within contemporary art is now more conceptual than ever. Artists do not intend to document unknown species, but simply to make visible the enormous loss of biodiversity that the Anthropocene is leaving us.

After becoming industrialized and capitalist societies, the speed and voracity with which we expanded on Earth, appropriating its territories and natural resources, began to cause dire consequences. There is no ecosystem that is not affected by this activity. The result has been the global ecological crisis that we are going through, but one cannot speak of an ecological crisis without finding its roots in a deep social crisis. We are not isolated individuals. We are part of a network of social, environmental and cultural relationships that build us. [2]

Artists such as Guiseppe Licari, Michael Wang or Carma Casulá make small contributions with their artworks in order to create ecological awareness. They give visibility to the spaces of resistance, in which they reflect on our relationship with the environment and what its dire consequences have been.

In the summer of 2015, Giuseppe Licari asked Rotterdam’s City Council not to cut the grass around the north of the Westersingel Green Corridor. The idea was to help the plants that live in the countryside, to develop and mature in the city, where they are normally considered as 'weeds'. A great variety of plants freely reproduced on domesticated lawns, proving that the greatest enemy of biodiversity is urbanisation. To document and inventory the number of wild plants that could grow spontaneously, Licari, with the help of botanist Remko Andeweg, dried and digitised one specimen from each of the 83 different plant varieties that had grown. Thus displaying an extensive herbarium of species that were resistant to the gardening regimes imposed by the city council.

Giuseppe Licari, Diversiteit. Courtesy of the artist.

In his exhibition “Extinct in New York” (2019), Michael Wang poses a similar proposal by recovering a selection of plants, lichens and algae, which historically grew wild in the natural environments of the city, but which have disappeared with urbanization in all its districts. In the months leading up to the exhibition, Wang planted and cared for the seeds and seedlings in his garden, then displayed them along with photographs of the process and a documentary account of its disappearance. Wang's intention was for the plants to remain in urban gardens after the exhibition closed.

Previously, the same artist developed the work “Extinct in the Wild” (2017) with flora that is no longer found in nature, such as the Blue Cycad (Encephalartos nubimontanus) or the Hawaiian Ōlulu (Brighamia insignis), but which has not become extinct thanks to the humane care. Plants that only survive in an artificial habitat. Labelled with the term "extinct in the wild," these species have left nature behind to enter fully into the circuits of human culture. This project also contained something very interesting conceptually, introducing living plant organisms as works of art to be cared for in the room by gardeners, scientists and visitors.

With the project “Monsanto no es santo de mi devoción” [Monsanto is not a saint of my devotion], artist Carma Casulà has been developing a memory bank with the stories of farmers about traditional cultivation since 2012. Seed banks, such as that of INIA (Spanish National Institute of Agrarian Research), have spent years collecting, storing and preserving the plurality of seeds that local horticulturists have selected for generations to improve their varieties. But in these banks, only seeds are collected, without documentation of the intangible knowledge from their cultivators. The benches that Casulà is building preserves not only the material aspect, but also the life system and the local culture associated with those specific farming techniques that have been passed down through the different generations and that mark the specificity of each territory. Through visual and literary narratives, the artist documents the farmers' direct experience.

Carma Casulà, Monsanto no es santo de mi devoción. Courtesy of the artist.

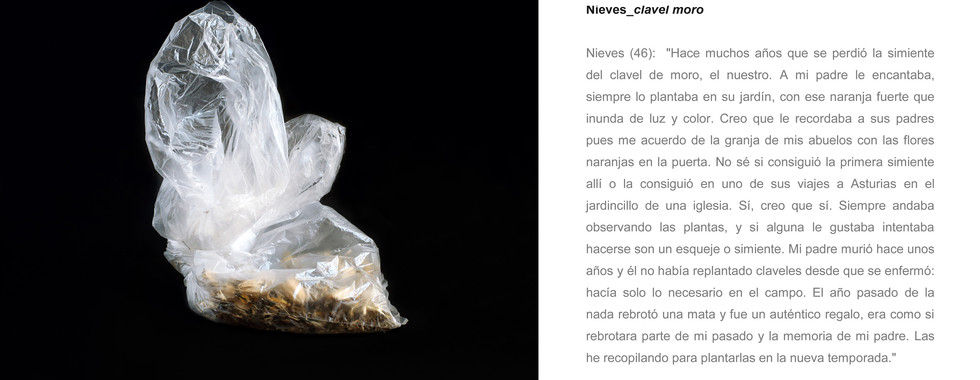

When observing Carma's herbaria, it is clear that they are contemporary still-lives, because in them, along with the seeds and plants, numerous artificial containers appear. Compared to traditional herbariums, in which everything represented was of biological origin, these works present inorganic materials and in, most cases, non-biodegradable.

Other examples of artistic work that documents plant extinction are the projects “Bioprospector” by Fernando García Dory (2010-) or “Planctum” (2015) by Jorge Fuembuena. Far from the idyllic and taxonomic organic representation, images of plants of our time are surrounded by synthetic, non-disposable or expensively recyclable materials: plastics, crystals, metals, and papers accompany the few living seeds that we still have.

As explained by Miguel Moñita, “nature has developed refined strategies for its survival over hundreds of millions of years, creating circular energy flows where no waste is produced, ensuring a balance that allows ecosystems to last.”[3] Therefore, we can say that contemporary herbaria, today more than ever, are documents of the disappearance of species that, in addition, collect reliable evidence of its causes.

The vegetal representations of yesteryear were 'Still Lives'. In them, everything was vegetal and therefore biodegradable; however, in contemporary representations, waste has begun to appear, materials created by the hand of man that can hardly be reintegrated in the process of generating life. We could say that today the herbaria are Memento mori, images that make mention of our own death.

As argued by Donna Haraway, “we know enough to reach the conclusion that life on earth that includes human people in any tolerable way really is over,”[4] and perhaps this is the opportunity to change this sad fate… Let's end this suicidal war against nature and build the iconography of another possible world inspired by it, let's grow towards the light, just like the vegetal, or let us extinguish ourselves by letting the plants develop in freedom.

To be nature or disappear, there are no other options.

[1] BLEICHMAR, Daniela(2012) El Imperio visible. Expediciones botánicas y cultura visual en la Ilustración hispánica. Fondo de cultura económica, Ciudad de Méjico 2016. pp.16-21

[2] SOTO SÁNCHEZ, Pilar. Arte, ecología y consciencia. Propuestas artísticas en los márgenes de la política, el género y la naturaleza. Tesis Doctoral, 2017 Universidad de Granada. p.45

[3] SÁNCHEZ-MOÑITA, Miguel. Imagen y sostenibilidad. Una aproximación a la representación fotográfica de la sostenibilidad desde una perspectiva artística. Tesis doctoral. Universidad Complutense de Madrid, 2017. p.215

[4] HARAWAY, Donna J. Staying with the Trouble: making kin in the Chthulucene, Durham: Duke University Press, 2016.p.4