- Apr 13, 2021

- 9 min read

Updated: Jan 15, 2023

INTERVIEW

Discrete Channel with Noise: Information Source #3, 2018

Courtesy Pompidou collection and Clare Strand

Clare Strand is a British conceptual artist based in Brighton, whose work constitutes a singular take on the meaning, context, and ambiguity of photographic images. Recently nominated for the Deutsche Börse Photography Award for Discrete Channel with Noise, Clare Strands’ research uses a series of different strategies – from found imagery to Kinetic machines, from algorithmic painting to mutoscopes – in order to push and expand the photographic medium.

Having as a starting point an interview with the artist published at ArchivoZine (Issue 17, THE VERNACULAR, In the Age of Media Culture, 2016), this is an excellent opportunity to get up to date and share Clare Strand's deeply stimulating and playfully experimental practice, where nothing about photography is definite and the unexpected is part of the creative process.

Ana Teresa Vicente (ATV) | About five years ago, on the occasion of your participation as an invited artist of the Post-Screen 2016: International Festival of Art, New Media, and Cybercultures (FBAUL-ULHT), we initiated a conversation about your artistic practice, conceptual ideas, and work strategies. At the festival main exhibition Unspoken Dialogues, (Fundação Millennium bcp, Lisbon, Portugal) you presented two artworks, The Seven Basic Prepositions and Conjurations Films. I would like to go back to the exchange we had at the time and propose a re-reading of the issues addressed then, to rethink and actualise them. In this context, I will start by asking about the central axis of your work, and what is that defines what you work with next.

Clare Strand (CS) | I would say, the central functions of photography and how it is used in any number of different contexts, but specifically the functional and utilitarian uses. What photography has been and where it is going. It’s failures and achievements.

ATV | Most of your artwork addresses the forms of vernacular imagery. How did vernacular photography become of your interest?

CS | I’ve collected images since I was young - kept in scrapbooks mostly. In retrospect, I can see where my interests and approach to imagery started forming. I appreciate the modesty and chameleon-quality that vernacular imagery has - how very amenable and generous, but at the same time how awkward and singular. Vernacular imagery is usually without context, it is ’nude’ and therefore open and vulnerable to interpretation and reading.

ATV | What role does research play in your practice? Does your practice shift or expands, depending on the subject matter you are working on?

CS | There is no simple conduit from research to practice. I’ve never seen research as a regular pattern. I prefer the analogy of my research being like rolling down a hill and coming to rest with the detritus of the journey being collected on my clothing. The research is the making as much as the making is the research.

ATV | Some of your works could be described as a kind of laboratory of thought on the decaying nature of the photograph, here explored by the intervention of a series of kinetic devices, like The Entropy Pendulum and Output for example. How do you see the introduction of these devices in your work?

CS | I find the sensibilities of the Surrealist, the Fluxus Group and the Conceptualist very appealing. I like the idea of art being mechanical, the result of a pre-planned recipe or a manifestation of the unconscious and the automatic. The Entropy Pendulum, is a good example of this approach, in that the experiment is determined, the stabilisers then come off and whatever subsequently happens is the right result.

The Entropy Pendulum and OutPut, 2015. Courtesy of Clare Strand

ATV | In a way, you have been exploring the effects of erosion and deterioration in photography, whether by scratching the surface of the print (The Entropy, Pendulum…), by pinning prints on a tree (that is the subject of the photographs themselves) and letting nature run its course (Rubbings), or by using a kind of animated Rolodex, to explore interference over/on the surface of the print. Is the creation of work being destroyed by itself something you were interested in exploring? How did you choose the different formats in which you ended up presenting the artwork?

CS | The works you refer to were first exhibited in my solo show, Getting Better and Worse at the Same Time (2015). As I mentioned, I have collected images - mostly utilitarian - and I like how these images exist in a contextual flux, a flux that is comparable to how we experience ‘images' in our shared networks. The pendulum was a way of thinking about the variability of the image. The Entropy Pendulum(2015) every day of the exhibit, scraps away at one of 36 silver gelatine, black and white images. After each day of degrading, the resultant image is then removed from the pendulum, placed in a frame on the gallery wall and replaced in the machine by another print for the process to restart the following day. Every time The Entropy Pendulum is exhibited the images come back out of their frames and undertake another evolution of erosion. The work becomes less and less, or perhaps more and more.

The Pendulum was a perfect mechanical action, as the whole exhibition was delivered as a binary proposition - better and worse, back and forward, black and white, up and down. The other machines and works in the exhibition were doing something similar. All of their identities were changing over the course of the show - all of their futures set and then unset, decided and then undecided, fixed by becoming broken and then becoming broken by being fixed.

ATV | The Happenstance Generator or The Seven Basic Propositions deal with the idea of coincidental nature that photography and data have acquired in our lives and the nature of our daily visual encounters. What was your initial motivation to make these projects?

CS | I made The Seven Basic Propositions in 2009. It’s a really basic web programme but sometimes the more stripped-down something is the more direct and coherent the message. I have a number of Kodak adds from the 50’s - a time when Kodak was abundantly active, encouraging the world to record itself. I found 7 Kodak propositions, which all started with ‘Because…’ Because Photography is Colourful, Because Photography is Inexpensive, Because Photography is Fast, etc. And I used these to generate google searches. The searches provide rather banal results and, in some ways, break down the ambitions of technology and distribution. The Happenstance Generator was again an attempt to think about the circulation of imagery - where an image can be important one moment and then redundant the next.

The Seven Basic Propositions, 2010. Courtesy of Clare Strand

ATV | The context of your work is the photographic medium itself – sometimes by turning things on their heads, or flipping the images around (I am thinking here of The 10 Least Most Wanted, for example); but also your experiments with aura or crime scene photography (photography as evidence), instruction manuals (utilitarian photography), or tabloid images, for example. There is also a relationship between playfulness, humour and absurdity/ madness in your work. Would you agree with this?

CS | It is important to me that my work establishes its autonomy. The 10 Least Most Wanted is a good example. As the production of a commission, I decided to edit ten of my favourite images from my scrapbook collection. These were my 10 most wanted images, or, in other words, the 10 images that made the most sense to me at the time.

I made a layout of them on my kitchen table and felt content enough with my choice. The next day I came back to them and turned one of the images over. I then turned the rest over realising now I preferred what was on their reverse. This series became the 10 Least Most Wanted and the paper scraps were encapsulated in thick acrylic and exhibited in a grand, museum-style vitrine. They are presented on a slight gradient - so the least wanted are shown face up and given priority. However, if you wanted to see the most wanted you have to bend down, crane your neck and peek in from behind the cabinet. For me, The 10 Least Most Wanted work is a perfect example of understanding the nature of the creative process – expressing that moment of chance, happenstance, luck, creativity, the flick of a wrist (whatever you want to call it). It is an outcome pitched somewhere between intention, accident and realisation.

The 10 Least Most Wanted, 2012. Courtesy Pompidou collection and Clare Strand, 2012.

ATV | Your work has been described as surreal and looking at your photographs and the images you collected on your clothing I am reminded of Paul Nougé’s photographs, where something seems to be documented but precisely what, in reality, we do not know. Is this a reference for you?

CS | I am intrigued with the surrealist and the Dadaist, I enjoy their idiosyncrasies, mandates, controversies, freedoms, gameplay, and suppression of conscious control over the process of making. I also enjoy the slow burn of things. I dislike work that leaves little room for air…

ATV | In a way, the pandemic exposed how electronic transmission can still be so faulty and unfulfilling. Things break down and disconnect, miscommunication abounds, there are distortion and lag. Your latest work, Discrete Channel with Noise, seems quite premonitory in this inadequacy, at the same time that it puts the human in the centre of the equation. It is a bit like the Telephone Game, where the received message differs substantially from the original. First, we have the codification of the selected images, then sending this code over video calls and, last but not least, the (sometimes fumbled) transmission is recorded, here by the means of paintbrushes. Was it important for you to place the human hand back into the process, with this act of painting?

CS | Since I can remember, I have needed a physical or mental image to make sense of a complex proposition. The noise of conversation and instruction can be easily countered by a simple sketch or diagram. Once I have a visual manifestation of a problem, I am far more able to think clearly. This can easily describe much of practice, Entropy Pendulum, Happenstance Generator, etc. Making the intangible, tangible helps my understanding. Assuming I’m not so different from the rest of the world, then perhaps this visualising process also works for others. Understanding the journey of the 'technical image’ in our networks via the methods of “traditional” image-making, for example, paintbrushes and paint may be somewhat absurd, but seemed an attractive and logical route. Putting myself at the centre of the project gave me first-hand experience of painting the 2928 pixels per painting and to in some ways encapsulating the labour and the instability of the networked image.

(left) Discrete Channel with Noise: Information Source #7, 2018

(right) The Discrete Channel with Noise: Algorithmic Painting; Destination #7, 2018

Courtesy Pompidou collection and Clare Strand

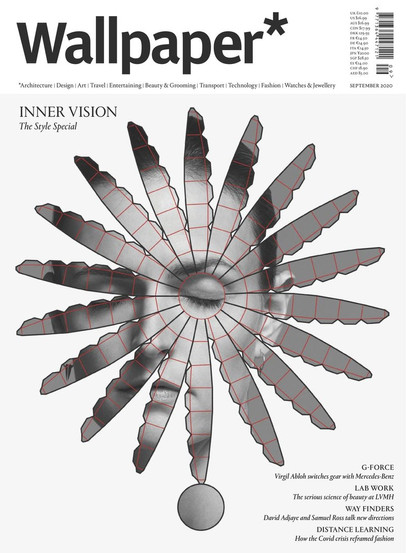

ATV | This idea of something tangible and putting yourself at the centre of the work, could it also be related to the Wallpaper commission? In a way, the readers were asked to or challenged to create 3D shapes from the templates, using their hands, to act upon the paper?

CS | There is a connection, The Wallpaper project, as you propose, is encouraging a transformation (from two to three dimensions). As in Discrete Chanel with Noise, there are extraneous variables that can affect the outcomes. However, in this case, I am not at the centre, the ‘user’ is. The work is ‘outsourced', to be made by hand or to be imagined. This is perhaps similar, to a recent zine I made with Multipress, "Negatives for Fun with Clare Strand's Photography."

Wallpaper Magazine, Cut and Fold, 2020

Negatives for Fun with Clare Strand's Photography, 2018.

Published by Multipress.

ATV | Following this idea of "outsourcing" your archive and the "production" or "outcome" of the work is very intriguing, especially when photography is so widely accessible but, at the same time, gets so intertwined with image processing techniques that are out of our reach, our understanding of what happens inside the machine. A bit like the Kodak slogan you previously used in The Seven Basic Propositions, except now it is "you press the button, the AI does the rest."

CS | The photograph as ‘artefact’ is indeed a diminishing consideration. However, the transmission and circulation of images and data still involves human interaction, as instigators at least. Though The Discrete Channel with Noise examines the sharing of imagery, I’m using this to explore data and information in general, what we voluntarily share on a daily basis, which can be interrupted, lost, corrupted, misdirected, trashed, altered and harvested. With Discrete Channel with Noise, I chose not to outsource but to put my own body directly into a supposedly ‘bodiless’ process, making a human-machine of myself and my husband. With the Wallpaper Cut and Fold project and the Negative zine, through outsourcing, I continue to think about ’the inside of the machine’ the transmission of data, and the noise between my proposition and the final outcome.

ATV | What are you working on right now? Would you allow us a little peek at your future projects?

CS | The 36 Output Images of The Entropy Pendulum also formed the selection pool of the source images for The Discrete Channel with Noise. I'm interested in how this grouping of images might mutate further to continue their journey. This year I start a new residency at the Royal Academy of Fine Arts and the Royal Conservatoire in Antwerp, where I shall start to work on a new and even more illogical phase with these images, involving musical score, costume and performance.

All images courtesy of Clare Strand, Pompidou Collection. www.clarestrand.co.uk

— Interview conducted by Ana Teresa Vicente.