- Jul 12, 2021

- 11 min read

Updated: Jan 15, 2023

PABLO LERMA

INTERVIEW

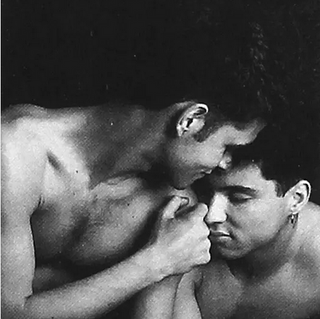

©Pablo Lerma, It Doesn't Stop at Images, 2020-ongoing.

Pablo Lerma is a Spanish artist, publisher and educator, currently living in Amsterdam, The Netherlands. In his artistic practice, Lerma works with archives and vernacular photographs creating installations and publications that approach themes such as queer identity, family representation and counter-narratives. In “It doesn't stop at images” (2020-ongoing), the artist delves into the archives at IHLIA - LGBTI Heritage, the biggest collection of information and images about the LGBTQIA+ community in Europe, looking for a different queer visual history, one in which he could see himself depicted. Moved by an archival impulse as Hal Foster would say, Lerma selects images of affection, love and relationships between men taken out of magazines, confronting the viewer with the matter of visibility/invisibility regarding the queer representativity in the media and history itself.

This interview is part of a series of conversations with the artists involved in the 'Pass it on. Private Stories, Public Histories' exhibition held at FOTODOK in 2020, curated by Daria Turminas, which can be viewed virtually here. This exhibition explores the constructed nature of memory, the complexity of its production and transmission processes. By presenting ongoing projects, it urges the viewers to question their relationship with archives, their content and possible meanings.

Archivo Platform (AP) | The work you've presented at “Pass it on. Private Stories, Public History” was not your first time working with archives and diving into this course of visual research. Could you tell us more about your experience with vernacular images?

Pablo Lerma (PL) | For the past 8 years, I’ve been developing work around archival images and vernacular photography. In previous projects, I incorporated these materials into my work in different capacities, until the moment that my photographic images stayed aside from my production and I started working exclusively with archival materials and vernacular photographs. “Greenfield. The Archive” is a project in a book form that was created with a found archive of hundreds of black-and-white negatives. In that project I worked as an “archivist” to develop the publication and revising concepts of power and representation through the collection of images I found in a flea market. Consequently, after that publication, my interest in archives continued evolving around these concepts of masculinity, queer representation and absence in the history of photography. That research resulted in a new body of work titled “A Frame of Darkness” where the strategies I followed to create photographic pieces derived from the “archivists” perspective of the previous work. Intervening, collaging, layering and modifying physically photographic prints and vernacular photographs brought a new way of working to my practice with archives.

In addition to my artistic practice, I’ve always been an avid collector of images from different sources and mediums. My connection with vernacular images does not only grow through the work I make in the studio, but it is also nurtured in my visits to flea markets, bookstores or digital wanderings on eBay or Markplaats, where I find authentic gems.

AP | Even though you’ve already created works derived from archival material, this was your first time working with a public queer archive. How did you start collaborating with IHLIA and what were you looking for in this turn from vernacular imagery to public archives?

PL | My collaboration with IHLIA was very fortuitous. I met Wilfred - the head of the collections at IHLIA - while playing in the gay basketball team in Amsterdam. We chatted briefly about IHLIA and he told me about the materials they had in their collections, so I became increasingly fascinated and intrigue to know more. Sometime later I was invited to exhibit my work at FOTODOK and it became interesting to me the chance to propose a research project between both institutions. I was always fascinated and hesitant to work with a queer archive. Fascinated because of the number of materials that can be found and work with. The work done by queer archives in terms of visibility, preservation and legacy towards the queer community is extraordinary, so I felt always hesitant because I was not sure what else I could add with my practice to this tremendous task they do.

Once my research began at IHLIA, I spent my first days in the books’ section. I did not know what I was looking for, I spent most of the days diving through the publications I found, trying to absorb and process the contents. After a few sessions there, I started feeling a sort of disappointment. Maybe my implicit expectations were not found … Maybe I was feeling visually exhausted… Maybe the majority of materials I consulted were distant representations of how I perceived my identity… I realized that a tremendous number of materials in the archives responded to a certain heteronormative way of representing queer individuals. The archive was coped with visual representations of nudity, intercourse, and disease, stereotypes that create a fragmented vision of an entire community. When moving into the magazine section, I started to find materials within that space that felt aligned with my own experience as a queer individual. Representations of concepts such as family, chosen family, affection, daily life, community, intersectionality, and more were found in these printed matter’s folders.

©Pablo Lerma, It Doesn't Stop at Images, 2020-ongoing. ‘Pass It On. Private Stories, Public Histories' at FOTODOK, 27.11.20-28.02.21 © Studio Hans Wilschut

AP | The archive at IHLIA originated from the research of the founders of Homologie, one of the magazines you've chosen to work with. Like any archive, these materials passed through a process of selection, which means choosing what will be preserved and what will not and, thus, creating a discourse regarding the queer legacy they want to perpetuate. How did you deal with these forms of visibility/invisibility within the archive you were working with?

PL | I believe any archive is constituted as an entity of power, a power that holds the right to represent, to make visible certain materials, communities, stories and parts of history. In that process of visibility, there is always something that is kept invisible and responds to certain politics in the archive. Who is managing the collections? Who is archiving the materials? Every person involved in the work of creation and preservation of an archive will use their own experience to shape the view and legacy of that specific archive. As Derrida mentions in Archive Fever: […] The archons are first of all the documents’ guardians. They do not only ensure the physical security of what is deposited and of the substrate. They are also accorded the hermeneutic right and competence. They have the power to interpret the archives. […]

In the process of working at IHLIA I had many conversations with Wilfred Van Buuren, the head of the collections. I wanted to understand the decisions behind certain materials collected to understand the history of the archive throughout the transformation in the last decades. Those conversations nurtured my research while in the archive because after receiving more explanations on certain parts of the collection I was able to ask better questions to myself and to the materials I consulted.

AP | There is a personal connection for you with this project since you've narrowed down the scope of the photographs to a time frame based on your birth decade (the 80s) and spaces you've lived in (Spain, the USA and the Netherlands). Even though, there is a relatable aspect of your work since it can be read as iconographic research in which many viewers hopefully will see themselves. Could you comment on that?

PL | I was born in the late 80s in Spain and grew up there for almost two decades before moving to the US and the Netherlands in subsequent years. My family is originally from the south of Spain, a very loving and open family but with a certain connection with religious traditions. Being an adolescent in the late 90s I remember seeing the first gay conductor on TV or visiting with my family a small town by the sea - outside of Barcelona – called Sitges, which is traditionally some sort of a gay resort in the south of Europe. Occasionally, I would visit Sitges during the summer with my family. I remember my fascination looking at these masculine hairy leather guys in the boardwalk at night in Sitges when I was an adolescent. However, I also recall hearing from my family words such as "faggot" when passing by these men. Those experiences, even though were transforming for me, made me create fragmented stereotypes of gay individuals.

When working at IHLIA, I was confronted again by those stereotypes and social constructions of sections in the queer community. That’s how I decided to look at them closely and try to understand the constructions of those identities from within the community and in relation to my own experience. For that purpose, I traced a time frame of three decades: '70s, '80s and '90s, and a location setting: the Netherlands, the US and Spain in order to conduct my research. I wanted to understand how my identity has been shaped by the communities and countries I lived in, but also in relation to a chronological moment in the queer community that gravitates around the decade I was born in.

©Pablo Lerma, It Doesn't Stop at Images, 2020-ongoing.

AP | In previous projects such as A frame of Darkness (2019) and You have shown me a strange image (2019), you also deal with photographs of gay individuals but most of the images preserve their identities as you've reframed them, intervened with collages or used negatives instead of the actual copies – what makes it harder to see their faces. But for It doesn't stop at images (2020-ongoing), you are working mainly with portraits taken from magazines and bluntly showing the displays of affection between men in a larger context. Nonetheless, the images that you chose are outside of the typical stereotype that surrounds queer individuals – such as sex, nudity, violence and objectified bodies. What can you tell us about this selection of images?

PL | The stereotypes you mentioned definitely haunt us. Haunt an entire community that is more than sex, nudity and disease. Our lives are full of many other things that have been erased from the representational images consumed by a heteronormative gaze. I could not continue perpetuating that approach in my practice because those images do not define me. I felt myself excavating in the archive and going through tons of materials and images until I found myself in them. I am committed to showing images of daily life, mundane pictures, those that show intimacy in a way that is not sexual, those that show the quotidian in a way that is not shocking, those that show tenderness and affection in a way that is familiar and not promiscuous, those that show struggle in a way that is not socially stigmatizing.

©Pablo Lerma, A Frame of Darkness, 2019-ongoing.

AP | As we look at your body of work, we get a strong feeling that it is pervaded by a will of creating counter-narratives regarding queer visual history. Matters of queer representativity have been approached in the art world for the past years. Still, it doesn't necessarily mean that the media has followed up this course into rethinking queer representativity in the public sphere. As you've worked with images from magazines from the '70s, '80s and '90s, do you feel that there has been any change in the way we perceive the LGBTQIA+ community through visual culture compared to more recent years?

PL | I want to believe there is more openness to queer representation in images nowadays, but sometimes I feel that the same standards and stereotypes are reproduced over and over. It is also difficult to compare printed pages to digital mediums because accessibility made us lose some specificity in the queer publications. In addition, there is some sort of gay melancholia inserted in the pages of the magazines I researched for this project, a feeling that times were better in the past, that some places became utopian such as San Francisco. But at the same time, I recognize that the work done there was done in order to have better, more visible rights in our days. It is paradoxical when I aligned these images from decades ago into a new current time and space to reflect on my own experience.

©Pablo Lerma, It Doesn't Stop at Images, 2020-ongoing.

AP | At the exhibition, you've presented three different tables in which the visitors could see a variety of images from distinct magazines but also within different frameworks, such as the literary and artistic representations of the gay community, the homosexual desire and how queer families and affection are depicted. In addition, each display is also made from two glass drawers with the original source material and your selection of images at different levels. On top of that, the upper glass works as a third layer, since it reflects the spectator and adds a new image to look into. This sort of topography gives the visitors a sense of depth and movement much needed to understand the necessary changing of stereotypes against the misrepresentation of the LGBTQI+ community, wouldn't you agree?

PL | I completely agree with this idea of understanding identities in a strata mode layering different experiences and signifiers to shape and change misrepresentations. The way the vitrine operated in the exhibition space was meant to replicate physically that experience. There was a first ground level – on wood – where original publications from the archive were shown. Following that level, there was a second one – on glass – where the selection of pictures I made was displayed creating constellations and framing the original materials shown in the level below. To finalise, I decided to include a third level – on glass – to provide the viewer with the reflection of themselves and their own experience when looking at the layers of materials showcased in the vitrine. In addition, the three layers on the vitrine were accessible in the front and back side of it in order to bring a sectional view of the strata in the archive and hopefully created a visual approach to this building of the representation of identity.

©Pablo Lerma, It Doesn't Stop at Images, 2020-ongoing. ‘Pass It On. Private Stories, Public Histories' at FOTODOK, 27.11.20-28.02.21 © Studio Hans Wilschut

AP | The title of your work is very provocative and gives us all something to think about discourses, visibility and representations regarding the LGBTQIA+ community while we are going through the images you've selected. What led you to title your project “It doesn't stop at images”?

PL | It doesn’t stop at images is a sentence mentioned at “Postcards from America” included in the book “Close to the Knives” by David Wojnarowicz. Regarding the original text and its context, Wojnarowicz argues how during the AIDS pandemic in the US media depicted a stigmatizing vision of the gay community and he uses the sentence: “It doesn’t stop at images …” to verbalise the frustration of a very narrow and sectioned representation of the gay community in such a fragile moment. For me, choosing this title for the exhibition operates as a trigger to challenge the viewer to look and think beyond the images they encounter in the project.

AP | At the FOTODOK exhibition, the projects were not only there for the public to see, but there were also scheduled talks with the visitors in which the artists would be available to discuss their process. During those talks could you grasp any of the visitor's reaction to the confrontation with the images you are proposing?

PL | Unfortunately, due to COVID-19, the show remained open only for about 3 weeks and then we went on a lockdown in the Netherlands. We could not have as many scheduled talks and visits as we wanted. However, I had a very interesting conversation during the opening day. I was in the space chatting with a few people and then a person approached me to talk about the 3rd vitrine on the show, titled On Community & Affection. In that vitrine you can see a variety of images that show tenderness, affection, family, couples, community, romance, and more … This person asked specifically about an image that was repeated twice – on purpose – of two men showing affection to each other. I was asked why that image was repeated twice and why we had to look at such a “cheesy” picture. In my understanding, that person felt triggered by affection, and that made me realise about the expectations people can have of queer representations. Side by side, there was a 2nd vitrine titled On Desire & Canons where any visitant at the show could see explicit images of nudity and sex, however those images did not trigger this person. Interesting how mundane images of daily queer lives can break the expectations and shock the audience.